|

|---|

by Francesco Franciosi and Joe Janzen, Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois

Corn and soybean prices have declined from historical highs in 2022 to long-run normal levels. (See: farmdoc daily May 31, 2022) After crop prices experienced a similar decline between 2012 and 2014, grain farms in the Corn Belt went through an extended period of low or negative net farm income. During this period, many farms covered losses by drawing down working capital, assets like cash or grain inventories that can be liquidated quickly to meet expenses. The liquidity provided by working capital allows farms continue operations in the face of losses, for example, by allowing them buy inputs necessary to plant the next year’s crop.

Looking ahead, University of Illinois farmdoc crop budgets for 2025 point to negative returns for corn and soybean farms. (See: farmdoc daily September 24, 2024) Should low returns persist, farmers may experience financial challenges similar to what they experienced post-2014. Grain farms in the US Corn Belt have built liquidity.

However, liquidity may differ widely across farms. In particular, younger farmers may be less liquid and therefore more exposed to economic downturns. Understanding the link between farm liquidity and business performance is key to weathering the possible downturn in the farm economy that lies ahead, especially if that downturn extends for multiple years.

This study analyzes the association between working capital built by farms up to 2014 and farm business performance during the subsequent low-price years from 2015-2018. Using data from Illinois FBFM, we follow the same farms over time. While profitability per acre varies widely across farms in our data, there are some economically meaningful differences in net farm incomes by baseline liquidity position. High liquidity farms tend to achieve better subsequent returns in difficult times, although there is some evidence that having very high liquidity levels is not associated with better performance.

Liquidity on Illinois Grain Farms

This study considers a set of common farm financial metrics. Specifically, we look at the following:

Liquidity measures how quickly a farm can meet its short-term obligations using its current assets – things like cash and items that can be sold quickly. Liquidity is commonly measured by considering current assets relative to current liabilities, so that liquidity can be compared across businesses.

Working capital per acre is a liquidity measure intended to be comparable across farm businesses. It is calculated as current assets minus current liabilities, divided by the total acres farmed. In simpler terms, it is the difference between what a farm owns and what it owes in the short term, normalized by farm size to enable comparison across different-sized operations. This metric indicates resources available to cover day-to-day expenses.

Net farm income (NFI) per acre represents the profitability of a farm relative to its size. It represents a return to operator’s labor and owned farmland. Higher NFI per acre indicates that a farm generates more income from each acre it manages.

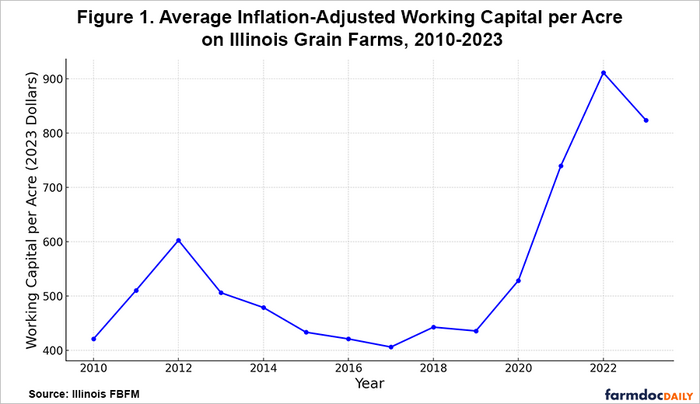

We contend that the period following 2014 provides important lessons about managing the farm through changing market conditions. Figure 1 shows trends in inflation-adjusted average working capital per acre on Illinois grain farms. Working capital peaked in 2012 and 2022, years with high commodity prices.

Even after adjusting for inflation, average working capital levels in 2022 are substantially higher than seen in the previous boom. After peaking in 2012, Illinois grain farms on average consistently drew down working capital for the next five years. The 2015-2018 period is the heart of this downturn, so our analysis sets 2014 as a baseline and considers farm performance between 2015-2018.

The annual averages shown in Figure 1 represent no individual farm; individual performance varies across time and across farms. Understanding how farms performed after they realized a particular level of liquidity, both high and low, reveals valuable lessons about farm financial management relevant to the current downturn in the farm economy.

Initial Liquidity and Subsequent Profitability in the Last Farm Economic Downturn

Our analysis considers how initial liquidity levels at the start of the last farm economic downturn were associated with farm performance in subsequent years. We consider Illinois grain farms who provide usable financial records to Illinois FBFM for every year from 2014 to 2018. This dataset contains 1,005 unique farms. We sort these farms by working capital per acre and divide them into five equal-sized categories (very low, low, medium, high, and very high).

Average 2014 working capital per acre for this subset of farms was -$88, $172, $369, $604, and $1,333 for the very low, low, medium, high, and very high categories, respectively.

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of farm performance by liquidity category over time. The figure shows not only typical or average profitability, but the distribution of net farm income across farms. The boxplots show both the median net farm income per acre (the middle horizontal line in each colored bar) and the range of outcomes for farms in each liquidity category by year. Fifty percent of farms lie within the interquartile range given by the colored bars.

|

|---|

Discussion

We find a consistent relationship between initial liquidity and subsequent farm performance during the last downturn in the US farm economy from 2015-2018. The initial liquidity position of farms in 2014 was related to differences in net farm income that increased over time. High liquidity was associated with more net farm income in 2015 and the gaps between very low, low, medium, and high liquidity farms grew in 2016, 2017, and especially 2018. This widening gap suggests that initial liquidity advantages may compound over time, as better-capitalized farms can both weather adversity and seize investment opportunities that lower liquidity farms cannot. For instance, higher liquidity farms may be able to make capital expenditures, buying machinery and land, when lower liquidity farms are struggling to cover short-run production costs.

We do find some evidence that more liquidity is not always better. Farms in the very high initial liquidity category tended to perform similarly to or worse than those in the high category. In 2017 and 2018, median net farm income for the very high category was actually lower than for the high category. This suggests some farms may lack productive investments in which to deploy excess liquidity. However, farms in the middle of the initial liquidity distribution demonstrated a consistent hierarchy, with medium liquidity farms maintaining a steady advantage over low-liquidity operations throughout the period. This pattern held through these challenging years, suggesting that medium and high levels of working capital provided meaningful benefits for operational stability.

Our findings have important implications for farm financial management as current forecasts suggest the next years may pose similar challenges for farm profitability as the 2015-2018 period. Our data suggests that maintaining adequate working capital serves both defensive and offensive purposes–protecting operations during downturns while enabling them to capitalize on opportunities when they arise. As farmers face another potential period of market pressure, these historical patterns offer valuable lessons about the importance of building and maintaining a strong liquidity position.