By Betty Resnick, Economist, American Farm Bureau Federation

This week, two continuing resolutions (CR) that would have kept the federal government operating after Dec. 20 have been introduced which included many things American farmers have been asking for: $21 billion in disaster aid, a farm bill extension, $10 billion in economic aid and year-round E-15. While the future of a CR is uncertain, the need for economic aid for farmers remains.

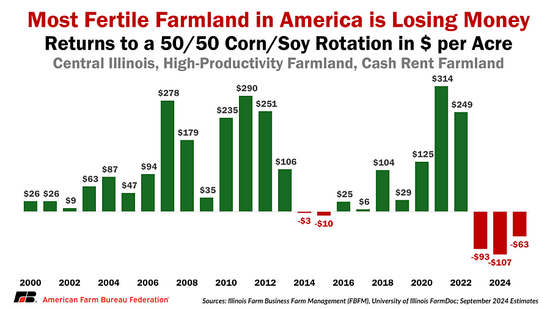

1. Farmers are entering their third year of losses on every acre they plant.

Since crop prices peaked in 2022, they have taken a nosedive. Corn and wheat are down 37%, soybeans down 28% and cotton down 22%. At the same time, input prices have remained high and sticky. As compared to 2020, the cost to produce an acre of corn has grown by nearly 30% nationally. When combined, many farmers are facing losses on every acre they plant. This is felt acutely. Data from the Farm Business Farm Management program at the University of Illinois illustrates this well. Farmers with a 50/50 corn and soy rotation on some of the very best cropland in the world will have faced an average loss of nearly $90 per acre between the 2023 and 2025 crop years. While farmers are familiar with a downturn, these deep, sustained losses are not manageable for many crop farmers across the country.

|

|---|

2. Thanks to inflation, the traditional farm safety net is ineffective.

American farmers have traditionally had a safety net in the farm bill that kicks in during tough times. Agriculture is inherently cyclical, so these safety net programs, including the Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs, provide help during down times so that farmers can stay in business today to support American families and the rest of the economy tomorrow.

Unfortunately, the mechanisms that make these programs work have not kept up with changes in input prices. The statutory reference prices have not been updated since the 2014 farm bill. In the last decade-plus, inflation has gutted the effectiveness of these reference prices. What you could buy for $1 in January 2014 would now cost $1.35, and programs carefully designed to provide just enough help in 2014 provide almost no help in 2024.

This outdated farm bill is not protecting farmers. Despite the difficult times farmers are finding themselves in, when accounting for inflation, 2024 is projected to have the lowest payments to U.S. farmers since 1982 – over four decades ago.

3. The net farm income picture is bleak.

In aggregate, net farm income has declined by $41 billion – nearly 25% – in only two years, according to USDA’s figures. While this number is striking on its own, it covers even steeper losses in the row crop sector with high returns in the livestock sector. The net cash income of farms specializing in corn, wheat and soybeans are down 42%, 43% and 44% respectively.

|

|---|

The agricultural industry is in recession. Farmers bear the brunt of this recession – but they are not alone. There have been thousands of layoffs throughout the agribusiness sector as well.

The lack of a new farm bill, which is two years overdue, has left farmers in a lurch during the sort of difficult stretch where they traditionally relied on the safety net. Due to the capital-intensive nature of farming, farmers rely on annual operating loans to plant their crops. Without some assurance of help from Congress and USDA, many farmers are at risk of losing access to credit and going out of business. The most vulnerable farmers – including beginning farmers, the next generation to grow our food – may be the first to lose their farms.